Did A Canadian Lake Kill The Mammoths?

By: Dean Taylor

The extinction of Mammoths and other North American megafauna is often credited to overhunting and has been a primary example of the extractive relationship between man and its environment. While this theory may have gained steam and has become a mainstay in popular culture, new theories have begun gaining traction suggesting that the truth behind what led to the extinction of some of North America’s most impressive mammals may be much more complicated than once thought.

Lake Agassiz

Lake Agassiz was an extremely large glacial lake present between 2.6 million and 11, 770 years ago. During this time period, massive glaciers covered the majority of present-day North America. One of the most impressive of these glaciers was known as the Laurentide, covering the majority of eastern North America and spanning an estimated 13,000,000 kilometres. When the eastern ice sheet, composed of roughly 25,000,000 cubic kilometres of ice, began to retreat north and reached the present day Canada-US border, massive amounts of water began to accumulate in the Red River Valley. This build-up of water continued for centuries as the ice continued to melt, eventually creating a lake that covered the majority of present-day Manitoba. As the ice sheet continued its retreat north, the lake continued to expand, eventually spreading to cover nearly all of Manitoba as well as significant portions of Saskatchewan, Ontario, North Dakota, and Minnesota.

Lake Agassiz

The Flood

As the climate continued to warm and the Laurentide continued to recede, the massive lake it left behind continued to grow. When the lake was at its largest, it was held in place by giant ice walls that were rapidly deteriorating. As the walls broke, the giant glacial lake began flooding into the sea. The path that the water took is still debated, however, the St. Lawrence in the east and the Mackenzie River Valley in the west are the primary suspects. No matter the direction in which it headed, the flood pushed roughly 9,000 cubic kilometres of fresh water into the Arctic Ocean, significantly hindering a cycle known as Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation.

Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation refers to the currents that are present in the ocean and are a major component of regulating the earth’s temperature. Stable temperatures are achieved when water from the depths of the tropics begins to rise and is warmed up. Once this water is warmed up, it begins moving northward in powerful currents such as the Gulf Stream. As the water makes its way north, it slowly begins losing its heat, warming up the areas it passes. As it reaches the arctic, this water cools down to the point of freezing, leaving behind cold, salty water that is dense enough to sink to the seafloor and begin its journey back south.

When Agassiz flooded, however, massive levels of freshwater spilling into the Atlantic significantly diluted the water in this critical area, causing the cycle to slow down or perhaps even stop. With the cycle grinding to a halt, much of North America was sent into another mini ice age, a period now known as the Younger Dryas.

The Younger Dryas

The Younger Dryas officially took place roughly between 12,900 and 11,500 years ago and came at a time when human hunters and mammoths were active on the landscape. In fact, these climate changes were so sudden that many believe they would have been felt in a single generation. As the mini ice age took place, temperatures were projected to have dropped around 12 degrees. While this number may seem insignificant, this sudden change caused massive food shortages in the northern areas that many large mammals inhabited, turning once lush grasslands into barren tundra.

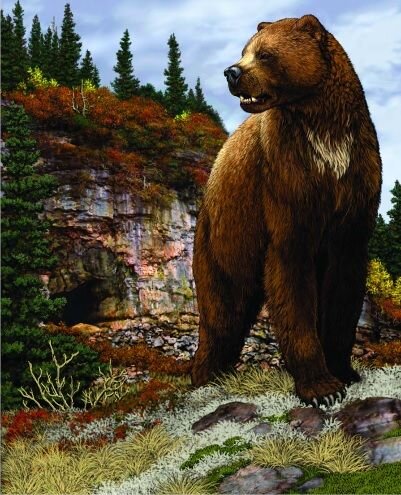

The loss of these food sources in such a short time is a well-supported culprit for the seemingly sudden extinction of Pleistocene-age herbivores such as the Wooly Mammoth and a giraffe-sized sloth, fittingly known as the Giant Ground Sloth. The sudden loss of these massive creatures off the landscape is also thought to have had a trickle-down effect on the larger predators that occupied the same area, explaining why Saber-toothed Tigers and Short-Faced Bears went extinct at roughly the same time, while smaller predators with smaller appetites were able to survive and remain on the landscape to this day.

Further Reading

The Lake Agassiz sparked climate change is just one theory behind the mass extinction of Pleistocene age mammals in North America. More on this theory can be found in the David J. Meltzer’s book First Peoples in a New World: Colonizing Ice Age America.

For more information on the over-hunting theory of Pleistocene extinctions, see Paul S. Martin’s Twilight of the Mammoths.

Other less supported but highly talked about theories include the Younger Dryas Impact theory and its resulting wide-spread wildfires. This theory is discussed at length in both peer-reviewed articles as well as the increasingly popular podcast The Joe Rogan Experience